Prophylactic oophorectomy (oh-of-uh-REK-tuh-me) significantly reduces your odds of developing breast cancer and ovarian cancer if you're at high risk. Weigh the pros and cons of this cancer prevention option.

Preventive surgery to remove the ovaries might be an option that people with a high risk of ovarian cancer and breast cancer might consider to reduce their risk. Preventive (prophylactic) bilateral oophorectomy carries benefits and risks that must be carefully balanced when considering this procedure.

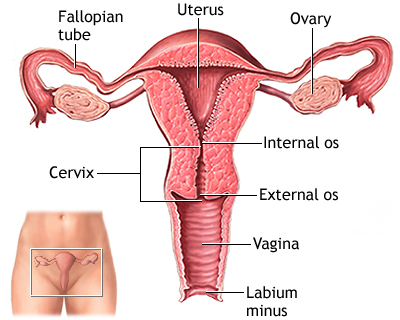

In an oophorectomy, a surgeon removes both your ovaries — the almond-shaped organs on each side of your uterus. Your ovaries contain eggs and secrete the hormones that control your reproductive cycle.

If you haven't experienced menopause, removing your ovaries greatly reduces the amount of the hormones estrogen and progesterone circulating in your body. This surgery can halt or slow breast cancers that need these hormones to grow.

Women with BRCA gene mutations usually also have their fallopian tubes removed at the same time the ovaries are removed (risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy) since they have an increased risk of fallopian tube cancer as well.

Preventive surgery for people with Lynch syndrome, also known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, may also include removing the uterus (hysterectomy) since they have an increased risk of endometrial cancer.

Prophylactic oophorectomy is usually reserved for those with:

-

Inherited gene mutations. People with a significantly increased risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer due to an inherited mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene — two genes linked to breast cancer, ovarian cancer and other cancers who have completed childbearing may consider this procedure.

People with other inherited gene mutations that increase the risk of ovarian cancer, including those with Lynch syndrome, might also consider this procedure.

- Strong family history. Prophylactic oophorectomy may also be recommended if you have a strong family history of breast cancer and ovarian cancer but no known genetic alteration. It might also be recommended if you have a strong likelihood of carrying the gene mutation based on your family history but choose not to proceed with genetic testing.

Discuss your risk factors for breast cancer and ovarian cancer with your doctor. Your doctor may recommend that you see a genetic counselor to discuss your family history of cancer to help you decide whether you should consider genetic testing and which genes should be included in the testing.

If you have a BRCA mutation, a prophylactic oophorectomy can reduce your:

-

Breast cancer risk by up to 50 percent in premenopausal women. As an example, if a woman with a high risk of breast cancer had a 60 percent chance of being diagnosed with breast cancer at some point in her lifetime, bilateral oophorectomy could reduce her risk to 30 percent.

Put another way, for every 100 women just like her, 60 could be expected to be diagnosed with breast cancer without oophorectomy. And 30 would be expected to be diagnosed with breast cancer after oophorectomy.

-

Ovarian cancer risk by 80 to 90 percent. As an example, if a woman with a high risk of ovarian cancer had a 30 percent chance of being diagnosed with ovarian cancer at some point in her lifetime, oophorectomy could reduce her risk to 6 percent, assuming an 80 percent risk reduction.

Put another way, for every 100 women just like her, 30 could be expected to be diagnosed with ovarian cancer without oophorectomy. And six would be expected to be diagnosed with ovarian cancer after oophorectomy.

In studies, the risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer varies according to the particular gene mutations that you have. And your individual risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer varies depending on many factors, including your age, your family history, your lifestyle choices and other strategies you're using to reduce your risk of cancer.

For some, oophorectomy may offer great reduction in risk. For others, the risks of surgery and the potential side effects may not be worth the reduction in cancer risk.

Oophorectomy is a generally safe procedure that carries a small risk of complications, including infection, intestinal blockage and injury to internal organs. The risk of complications depends on how the procedure is performed.

But more concerning is the impact of losing the hormones supplied by your ovaries. If you have yet to undergo menopause, oophorectomy causes early menopause. Early menopause carries many risks, including:

- Bone thinning (osteoporosis). Removing your ovaries reduces the amount of bone-building estrogen your body produces. This may increase your risk of a broken bone.

- Discomforts of menopause. Hot flashes, vaginal dryness, sexual problems, sleep disturbance and sometimes cognitive changes can occur during menopause. Removing your ovaries doesn't mean you'll immediately have these problems, but it does mean that any menopausal symptoms you develop will occur earlier and are more likely to reduce your quality of life than if they occurred during natural menopause.

- Increased risk of heart disease. Your risk of heart disease may increase if you have your ovaries removed.

- Lingering risk of cancer. Prophylactic oophorectomy doesn't completely eliminate your risk of breast cancer or ovarian cancer. A type of cancer that looks and acts identical to ovarian cancer can develop after the ovaries and fallopian tubes are removed. The risk of this type of cancer, called primary peritoneal cancer, is low — much lower than the lifetime risk of ovarian cancer if the ovaries remain intact.

Prophylactic oophorectomy might relieve much of your anxiety about developing cancer, but this type of surgery can also take an emotional toll on you. Even if you didn't plan on having children, you might mourn the loss of your fertility.

Use of low-dose hormone therapy after oophorectomy is controversial. While studies have shown that use of hormone therapy after menopause may increase the risk of breast cancer, other studies suggest early menopause can cause its own serious risks.

Women who undergo prophylactic oophorectomy and don't use hormone therapy up to age 45 have a higher rate of premature death, heart disease and neurological diseases. For this reason, doctors typically recommend that younger women who have surgically induced menopause should consider taking low-dose hormone therapy for a short time and stop around age 51.

It isn't entirely clear what effect hormone therapy might have on your cancer risk. Several studies have found that short-term hormone therapy doesn't increase the risk of breast cancer in those with BRCA mutations who have undergone prophylactic oophorectomy. Ask your doctor about your particular situation. If you decide to take low-dose estrogen, plan to discontinue this treatment around age 51.

You may opt to have your uterus removed during your oophorectomy surgery so that you can take a type of hormone therapy (estrogen-only hormone therapy) that may be safer for those with a high risk of breast cancer. Discuss the benefits and risks of hysterectomy with your surgeon.

Researchers are studying other ways to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer in people who have a high risk of the disease. But these other ways of preventing ovarian cancer haven't been proved to reduce risk as much as oophorectomy has. For this reason, most doctors recommend oophorectomy.

But oophorectomy isn't right for everyone with a high risk of breast cancer or ovarian cancer. So talk about the alternatives with your doctor to better understand how they may affect your risk. Options include:

-

Increased screening for ovarian cancer. You may choose to have ovarian cancer screening once or twice each year to look for early signs of cancer. Screening usually includes a blood test for cancer antigen (CA) 125 and an ultrasound exam of your ovaries.

In theory, increased screening should be able to help doctors catch ovarian cancer at its earliest stages, but whether that's possible with current screening methods isn't clear. Screening tests are noninvasive, but there's no evidence that they save lives.

-

Birth control pills. Studies suggest that taking birth control pills reduces the risk of ovarian cancer in average-risk women. There is good evidence that birth control pills can also be beneficial in high-risk women, such as those with BRCA mutations.

There is concern that newer birth control pill formulations are associated with a very small increase in the risk of breast cancer. However, the benefits of reducing ovarian cancer risk seem to outweigh the small risk of breast cancer.

Yes. Surgery to remove your breasts (bilateral mastectomy) may reduce your risk of breast cancer by 90 percent. As an example, if your risk of developing breast cancer at some point in your lifetime is 50 percent, a preventive mastectomy may lower your risk to 5 percent.

Put another way, for every 100 women with that same level of risk who undergo preventive mastectomy, five could be diagnosed with breast cancer at some point in their lives.

Reasons you might choose oophorectomy over mastectomy include:

- Oophorectomy reduces your risk of two cancers. For those that haven't yet experienced menopause, oophorectomy reduces the risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer, while mastectomy reduces only the risk of breast cancer.

- There aren't many options for preventing ovarian cancer. Ovarian cancer is sometimes seen as a greater threat than breast cancer because it isn't easily detected, and it may be detected at a later stage when diagnosed. While there's no proven method for finding ovarian cancer at an early stage, there are tests, such as mammograms and breast MRIs, to detect breast cancer at an early stage in very high-risk women.

- Removing your ovaries doesn't affect your appearance. Some women are concerned about how they'll look if they have their breasts removed. Oophorectomy won't affect your appearance.

These benefits have to be balanced against the risks of oophorectomy and the early menopause that occurs as a result.

The decision to have prophylactic oophorectomy is a challenging and difficult one with no clearly right or wrong answer. It comes down to a personal choice you alone can make, but advice from a genetic counselor, a breast health specialist or a gynecologic oncologist can help you make a more informed decision.

Questions to ask your doctor or other health care provider include:

- What is my risk of breast cancer?

- What is my risk of ovarian cancer?

- What are my options to lower my risk of breast cancer?

- What are my options to lower my risk of ovarian cancer?

- What are the benefits and risks of each option?

- What are some good sources of information about reducing my cancer risk?

- How much time can I take to research my options and make a decision?

- If I decide that prophylactic oophorectomy isn't right for me right now, can I change my mind later?

- What advice would you give your friend or family member if she were in my situation?

Determining whether prophylactic oophorectomy is right for you — and when it might be right for you — depends on your individual risk of cancer and how aggressive you want to be in your cancer prevention efforts.

Established risks:

- Being a Woman

Just being a woman is the biggest risk factor for developing breast cancer. There are about 266,120 new cases of invasive breast cancer and 63,960 cases of non-invasive breast cancer this year in American women.

- Age

As with many other diseases, your risk of breast cancer goes up as you get older. About two out of three invasive breast cancers are found in women 55 or older.

- Family History

Women with close relatives who've been diagnosed with breast cancer have a higher risk of developing the disease. If you've had one first-degree female relative (sister, mother, daughter) diagnosed with breast cancer, your risk is doubled.

- Genetics

About 5% to 10% of breast cancers are thought to be hereditary, caused by abnormal genes passed from parent to child.

- Personal History of Breast Cancer

If you've been diagnosed with breast cancer, you're 3 to 4 times more likely to develop a new cancer in the other breast or a different part of the same breast. This risk is different from the risk of the original cancer coming back (called risk of recurrence).

- Radiation to Chest or Face Before Age 30

If you had radiation to the chest to treat another cancer (not breast cancer), such as Hodgkin's disease or non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, you have a higher-than-average risk of breast cancer. If you had radiation to the face at an adolescent to treat acne (something that’s no longer done), you are at higher risk of developing breast cancer later in life.

- Certain Breast Changes

If you've been diagnosed with certain benign (not cancer) breast conditions, you may have a higher risk of breast cancer. There are several types of benign breast conditions that affect breast cancer risk

- Race/Ethnicity

White women are slightly more likely to develop breast cancer than African American, Hispanic, and Asian women. But African American women are more likely to develop more aggressive, more advanced-stage breast cancer that is diagnosed at a young age.

- Being Overweight

Overweight and obese women have a higher risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer compared to women who maintain a healthy weight, especially after menopause. Being overweight also can increase the risk of the breast cancer coming back (recurrence) in women who have had the disease.

- Pregnancy History

Women who haven’t had a full-term pregnancy or have their first child after age 30 have a higher risk of breast cancer compared to women who gave birth before age 30.

- Breastfeeding History

Breastfeeding can lower breast cancer risk, especially if a woman breastfeeds for longer than 1 year.

- Menstrual History

Women who started menstruating (having periods) younger than age 12 have a higher risk of breast cancer later in life. The same is true for women who go through menopause when they're older than 55.

- Using HRT (Hormone Replacement Therapy)

Current or recent past users of HRT have a higher risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer. Since 2002 when research linked HRT and risk, the number of women taking HRT has dropped dramatically.

- Drinking Alcohol

Research consistently shows that drinking alcoholic beverages -- beer, wine, and liquor -- increases a woman's risk of hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer.

- Dense Breasts

Research has shown that dense breasts can be twice as likely to develop cancer as nondense breasts and can make it harder for mammograms to detect breast cancer.

- Lack of Exercise

Research shows a link between exercising regularly at a moderate or intense level for 4 to 7 hours per week and a lower risk of breast cancer.

- Smoking

Smoking causes a number of diseases and is linked to a higher risk of breast cancer in younger, premenopausal women. Research also has shown that there may be link between very heavy second-hand smoke exposure and breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women.

- Emerging risks:

Low of Vitamin D Levels

Research suggests that women with low levels of vitamin D have a higher risk of breast cancer. Vitamin D may play a role in controlling normal breast cell growth and may be able to stop breast cancer cells from growing.

- Light Exposure at Night

The results of several studies suggest that women who work at night -- factory workers, doctors, nurses, and police officers, for example -- have a higher risk of breast cancer compared to women who work during the day. Other research suggests that women who live in areas with high levels of external light at night (street lights, for example) have a higher risk of breast cancer.

- DES (Diethylstilbestrol) Exposure

Some pregnant women were given DES from the 1940s through the 1960s to prevent miscarriage. Women who took DES themselves have a slightly higher risk of breast cancer. Women who were exposed to DES while their mothers were pregnant with them also may have slightly higher risk of breast cancer later in life.

- Eating Unhealthy Food

Diet is thought to be at least partly responsible for about 30% to 40% of all cancers. No food or diet can prevent you from getting breast cancer. But some foods can make your body the healthiest it can be, boost your immune system, and help keep your risk for breast cancer as low as possible.

- Exposure to Chemicals in Cosmetics

Research strongly suggests that at certain exposure levels, some of the chemicals in cosmetics may contribute to the development of cancer in people.

- Exposure to Chemicals in Food

There's a real concern that pesticides, antibiotics, and hormones used on crops and livestock may cause health problems in people, including an increase in breast cancer risk. There are also concerns about mercury in seafood and industrial chemicals in food and food packaging.

- Exposure to Chemicals for Lawns and Gardens

Research strongly suggests that at certain exposure levels, some of the chemicals in lawn and garden products may cause cancer in people. But because the products are diverse combinations of chemicals, it's difficult to show a definite cause and effect for any specific chemical.

- Exposure to Chemicals in Plastic

Research strongly suggests that at certain exposure levels, some of the chemicals in plastic products, such as bisphenol A (BPA), may cause cancer in people.

- Exposure to Chemicals in Sunscreen

While chemicals can protect us from the sun's harmful ultraviolet rays, research strongly suggests that at certain exposure levels, some of the chemicals in some sunscreen products may cause cancer in people.

- Exposure to Chemicals in Water

Research has shown that the water you drink -- whether it’s from your home faucet or bottled water from a store -- may not always be as safe as it could be. Everyone has a role in protecting the water supply. There are steps you can take to ensure your water is as safe as it can be.

- Exposure to Chemicals When Food Is Grilled/Prepared

Research has shown that women who ate a lot of grilled, barbecued, and smoked meats and very few fruits and vegetables had a higher risk of breast cancer compared to women who didn't eat a lot of grilled meats.

References

- Muto MG. Risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in women at high risk of epithelial ovarian and fallopian tubal cancer. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Jan. 11, 2018.

- AskMayoExpert. Risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Rochester, Minn.: Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; 2017.

- AskMayoExpert. Genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Rochester, Minn.: Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; 2017.

- AskMayoExpert. Ovarian cancer screening. Rochester, Minn.: Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; 2015.

- Rocca WA, et al. Premature menopause or early menopause and risk of ischemic stroke. Menopause. 2012;19:272.

- De Felice F, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutated patients: An evidence-based approach on what women should know. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2018;61:1.

- Mørch LS, et al. Contemporary hormonal contraception and the risk of breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377:2228.